There might be affiliate links on this page, which means we get a small commission of anything you buy. As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases. Please do your own research before making any online purchase.

An assumption underlying the science of positive psychology is that happiness can be measured.

There is the Bhutan Happiness Scale. There is the Subjective Happiness scale. And there are constant studies that measure happiness. But nothing really measures your personal happiness very well. So all measures of happiness are based on averages from what people report during interviews with psychologists after specific experiments.

We are guild of it here on DGH too. Just look at some of the articles we have where we talk about ways to increase happiness.

Gratitude journals increase well-being…

Money does little for happiness…

Positivity can prevent divorce…

Yelp is more trustworthy than your brain…

Buying many small items is better than buying a few large things…

Prove that assumption false, and hundreds of research findings fall apart into meaningless garble.

In this post, we will take a deep look at the science behind measuring happiness and see if it is these measurements have any value at all…

A happiness measurement is a requirement for growth.

Without measurement, growth stops. For example, if you want to lose weight but you don't measure yourself, you'll have no way of knowing if what you're doing is working. The more precise the measurement, the faster and more accurately you'll know if something is working or not. That's why instead of trying to eyeball your weight with a mirror (which counts as a measurement but is crude), you might use a bath scale.

Because we care about life satisfaction and well-being, happiness measurement is something that we're always doing, consciously or not. Our emotions are a measurement, although often crude, of how well we're doing with our life.

Most of the time we base our decisions on that crude measurement, hoping our internal barometer gets it right.

Sometimes it does, “Playing tennis with Mike and Steve last night was fun and made me happy. Let's do it again!”

Sometimes it doesn't, “Masturbating to naked pictures of hot girls was fun and made me happy… let's do it again and again!”. In this case, there is reason to believe that we repeatedly misremember masturbation as having been more pleasurable than it actually was.

Because our internal barometer (that is, our emotions like desire) often gets things wrong, we listen to advice from others, “Amit, I know you feel that snorting cocaine will make you happier, but trust me – I know from experience – you'll regret it.” (That was an imaginary conversation that's never actually happened.)

But the barometer of the experienced isn't always accurate. My aunt and uncles often tell me (with a loud voice at point-blank range) that I need to marry a fellow Gujrathi Indian – only then will I have a happy marriage. Are they a good source of advice? They've got years of experience on me, but they've been blindsided by cognitive dissonance. In general, their marriages suck.

That's why surveys can be useful – they aggregate the wisdom of thousands. Of course, the accuracy of those surveys is an open concern.

Likewise, this is why money is useful – money is a barometer of happiness. We assume that money will lead to greater things, so we try to acquire more of it. In general, this strategy will help more than it hurts. But money, like survey reports of happiness, is an inaccurate barometer of happiness.

In part 2 of this post (to be released in December) , I'll cover the specific ways in which money fails to accurately measure well-being.

Do happiness surveys accurately capture the happiness and well-being of its participants, or would we be better off listening to expert opinions from other fields, like self-help or economics?

Here's the truth – the measurement of happiness is a hot mess. It's inaccurate, incomplete, and often inappropriately interpreted.

Article length – 6,000 words. Summary & table of contents (click to show).

There are a number of issues complicating the accurate measurement of happiness. In this article, I first cover the six which pose the largest challenges, and then the evidence which suggests that despite the problems, happiness research is still valuable.

One – there's more to life than satisfaction. Although those who report high life satisfaction are also likely to have significant differences in more objective variables, like the number of close friends they have and their sleep quality, there are a number of important life components ignored by the question. For example, many who report high life satisfaction are poor, in bad health, or feel lost. We care about those things, and yet happiness surveys fail to capture much of that information (although so too does wealth and income).

Two – survey questions are so cognitively challenging that we subconsciously replace them with easier ones. When people are asked to assess the quality of their life, one possible approach would be assessing the quality of all areas of their life that are important to them over the past few months (e.g. the quality of their marriage, their bosses behavior, and the weather over past 12 weeks). But that kind of assessment is difficult. So instead, most people (without realizing it!) substitute the question they were asked with an easier one.

Instead of answering, “all things considered, how satisfied are you with your life as a whole these days?”, they answer, “how do you feel about your life?” That's a dangerous substitution, because in this matter, our feelings are extraordinarily inaccurate. People answer a question about how their life has been over the past few months based on their present mood. For example, give people a dime, and they'll report higher life satisfaction. Because the dime made them feel good, their judgement of their life as a whole gets colored more positively. Have the surveys handed out by beautiful models, and suddenly the happiness of the entire country would increase.

Three – our memory of past events is incomplete. How much a person reports having enjoyed an experience can be predicted with just a few pieces of information – how they felt during the most memorable experiences, and how they felt during the end. Emotional information about the quiet and mildly pleasant reclining at the beach gets faded; emotional information about the crazy party gets amplified. This is a problem because happiness data is getting deleted – someone who goes on crazy vacations punctuated by long hours at a job they hate might report higher life satisfaction than someone with a more normal life, but in fact the person with the more normal life might have had more total pleasant experiences (they just weren't as intense).

Four – most positive psychology studies use ineffective placebos. If a person is doing something they think is supposed to make them happier, they might become happier, even if that thing that they're doing is actually useless. For example, sugar pills painted as Tylenol can reduce pain – the subconscious will do some work on its own, without external chemical assistance. Because many positive psychology studies have poor placebos, its difficult to determine if a person is improving because the intervention is effective, or because they think they're supposed to become happier. Placebo treatment is undesirable because it is inconsistent, uncontrollable, and often only marginally useful.

Five – psychologists often measure so many variables that due to statistical coincidence, some publishable result will be found even when no real discovery has been made. For example, the results of ten coin flips can't be predicted based on the weather. But if you measure the weather, your flip speed, the height the coin went, which face was originally showing, the result of the previous flip, and a thousand other variables, something is bound to come up with an apparent relationship to the coin flips. This relationship was a coincidence – repeat the experiment, and the magic variable will stop accurately predicting the coin flip. Unfortunately, many positive psychology experiments don't get repeated.

Six – due to social benchmarking, a person might report being happy even when they're actually not. For example, it might be culturally taboo to report unhappiness. Or it might be expected that the person be miserable at work. In which case, because unhappiness is the expectation, they'll report being satisfied with their job, even when they're not.

But despite these problems, there's hope!

The results of happiness surveys do:

1) correlate with more objective measures of things we care about, like smiling frequency and health, and

2) can be used to successfully predict the outcome of other things we care about, like the likelihood of divorce or getting a new job.

Although the correlations are often weak, the next best alternative is often just as bad or worse. Stay tuned for post two of the series, which discusses the faults of using wealth and income as a measure of well-being and welfare as mercilessly as I discussed the faults of using positive psychology for that purpose.

Also, given time, the reliability of happiness measurement will increase, as psychologists aware of these problems devise better methods, like the day reconstruction technique and the experience sampling method.

Strike One – There's More to Life Than Satisfaction

A typical survey might ask, “taking all things together, how happy would you say you are?”

A useful question, but faulty.

When most people hear the word “happy”, they think “positive emotion”. They think, “taking all things together, how much positive emotion have I been experiencing?”

There's more to life than feeling good, so to counter that problem, researchers ask about life satisfaction.

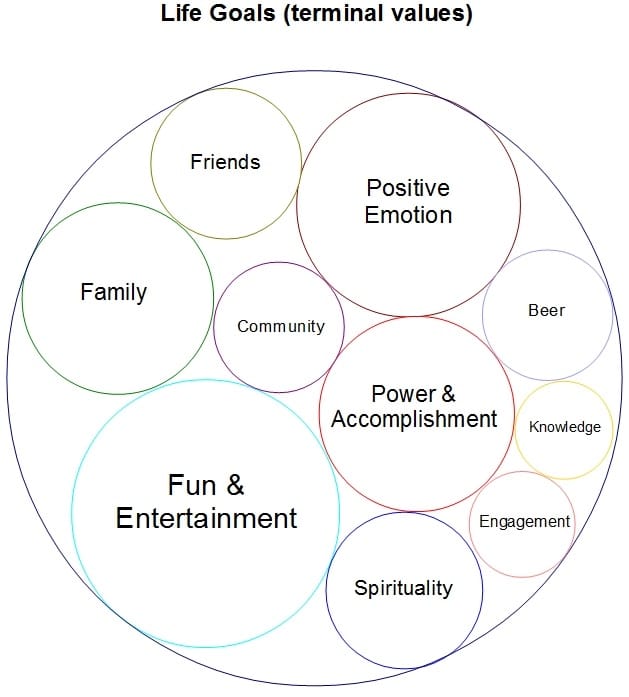

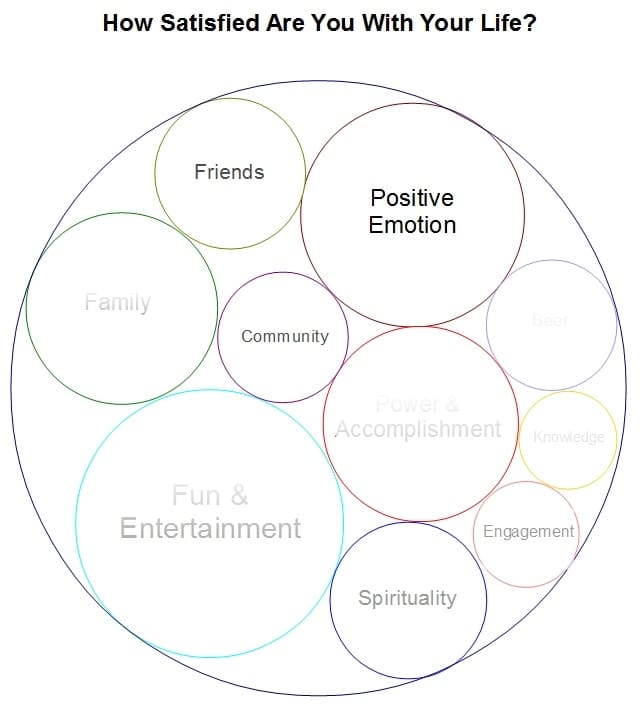

Unfortunately, for reasons discussed in Strike Two, people give almost the same answer to, “how satisfied are you?” as they do to, “how happy are you?” That means that happiness surveys are touching only a small, albeit important, subset of life goals. For example, a hypothetical American might care about:

When a happiness survey captures the amount of positive emotion a person has felt, what other aspects of his life does the survey capture information on?

1. Some of the things that we care about are directly related to the amount of positive emotion we feel. Someone with lots of fun and caring friends will be happier, so asking people how happy they are will capture information about both things they care about – feeling a positive emotion, and having quality friendships.

2. Some of the things that we care about are on average unrelated to the amount of positive emotion we experience. For example, according to most happiness surveys, having children has on average, almost no impact on happiness and life-satisfaction.1

3. Some of the things that we care about have an opposing effect. Past a certain point, the pursuit of power interferes with the pursuit of positive emotion.2 Likewise with the pursuit of meaning.3 Helping others and working to make the world a better place will increase happiness… but I know folks in non-profit who work 12 hour days. They're making a sacrifice.

4. Some of the things that we care about have an impact on mood which is quickly lost. According to happiness surveys, three years after marriage, most couples are as happy as they were before they met their partner.4 Likewise with many other things – with time, I adapted to my poor health. Does the fact that I'm happy despite my health mean that my poor health doesn't matter? Does the fact that people's moods even out after a few years of marriage mean that their spouse is useless?

No, absolutely not. So when positive psychologists ask, “how satisfied are you with your life?” that question is capturing only a portion of what it ideally would.

That means that even though Denmark reports being the world's happiest country, there are areas where it could be lacking, which wouldn't be reflected in their response to the question, “how happy are you?”

In my case, it's important to me to work long hours, be sleep deprived, and eat $1 ramen, which is why I choose to move to Silicon Valley and start my own business.

Strike Two – Don't Change The Question!

I've got two questions for you.

One – what's the weather been like the past few days?

Awesome, okay, gloomy?

It's an important question.

Got an answer? Okay, next.

Two – how happy are you?

Very happy? A little happy? Not happy?

Take a moment to think of an answer.

*

*

*

*

*

*

Have you thought of your answer?

*

*

*

*

*

*

Great.

A common problem people have with measuring happiness is that happiness means different things for different people.

True. Also true – happiness means different things for the same people at different times.

Although you might not believe me, for some of you, my asking about the weather influenced your response to the question, “how happy are you?”

“The mood you are in determines more than 70 percent of how much life satisfaction you report.” -Martin Seligman

In one study, participants were asked a number of questions, including two questions similar to the ones I asked you above.5

- On a scale of 1 to 5, how happy are you these days?

- How many dates did you have last month?

Surprise – there was no statistically significant correlation between the answers to the two questions.

Zero dates or five dates, on average it made no difference to how happy people reported being.

The experiment was run again, but the order of the two questions was flipped:

- How many dates did you have last month?

- On a scale of 1 to 5, how happy are you these days?

This time, there was a correlation of .66 – the number of dates the subject had been on was strongly related to their self-reported happiness.

Is this a case of self-delusion? Of nerds pretending to themselves that they're okay with being unloved until a painful reminder by a survey question forces them to confront reality?

No, not at all. The reason single people can be as happy as those in a relationship, and the reason people living in cold Canada can be as happy as people living in warm Florida, is because:

- Cold or hot, single or in a relationship, we partially adapt to our circumstances.

- Most of the time, we're not thinking about the weather or our relationship status – we're absorbed with our work, our hobbies, the traffic, our friends, the TV, and other mundane things.

So then why did asking how many dates a person had been on right before asking about their happiness have such an outsized impact?

The technical term is the affect heuristic. In layman's terms, “that question is too hard, so I'm going to answer something easier.”

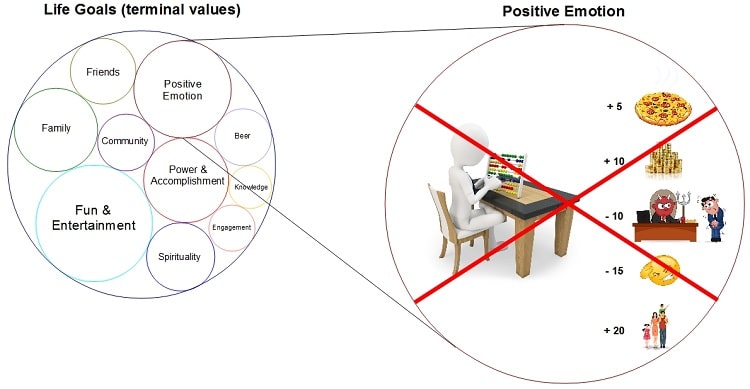

Our brain doesn't keep a running tally of happiness points, which get added to or subtracted from as good or bad things happen.

If not, then how does our brain provide an answer to the question, “how happy am I these days?”

It could crawl back over our recent memories and then take an average of the emotions experienced, but that's still too hard – in a matter of moments, the brain would have to go over thousands of memories.

Instead, it replaces the difficult question, “how happy am I these days?” with an easier one, “how does thinking about my life make me feel?”

We know this is true because momentarily changing how a person feels changes how they feel about their life as a whole.

One – there's the dating example above. Influencing mood by drawing attention to success or failure in the dating arena influenced answers to questions about long-term happiness.

Two – letting subjects serendipitously discover a dime changed their response to happiness and life satisfaction questions. A dime shouldn't transform a “I've been happy over the past year” to an “I've been very happy over the past year”, but it does.19

Three – this bias can be found in all sorts of situations, outside of happiness research. Daniel Kahneman provides a number of examples in his book, Thinking, Fast and Slow. For example, a CEO might decide whether or not to purchase another company based on how thinking about that company makes him feel, rather than on the financial implications for his firm – how he feels can be impacted by things which have nothing to do with financial implications, like the attractiveness of company's CEO.6

Strike one – life satisfaction and happiness questions capture only a portion of what's important, getting mostly data on positive emotion.

Strike two – the data on positive emotion is itself only a fraction of the real picture.

Why does that matter and what's going on in the diagram above? The next section explains it all.

Strike Three – I Can Only Remember a Few Things…

In the section above, you learned that the question “how happy are you these days?” gets substituted with, “how does thinking about your life make you feel?”

You also learned that the substituted question is heavily influenced by the person's mood at the time of answering.

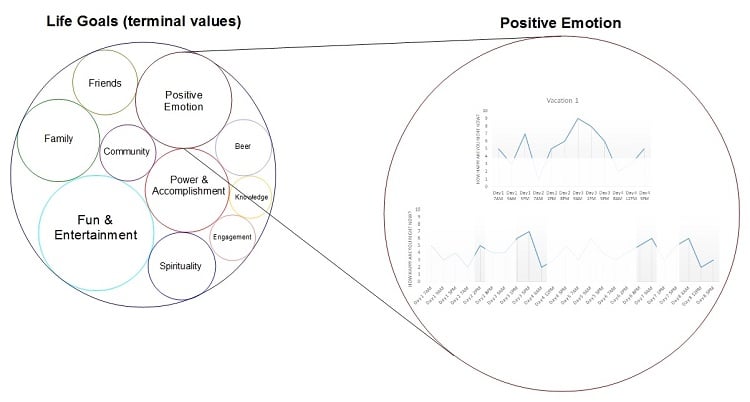

We can find out the other ways in which the question is imperfect by using the next best thing to a happiness abacus – the experience sampling method (ESM).

ESM is a new type of happiness measurement. The typical survey asks participants how happy they've been over the past few weeks. With the ESM, scientists randomly text message participants several times a day. Each time, they ask, “what are you doing and how do you feel?”

Because the questions being asked are for most people easy, this method is immune to question substitution and the imperfections of memory:

- What are you doing? I'm writing a blog post.

- How do you feel? Happy, engaged, and excited.

Now, average together the results of the ESM and then compare against the results of the survey questions. If a person responds to the survey that they are very happy, and if on average they respond to the ESM that they are very happy, we know that the survey question is a reliable indicator of day-to-day positive emotion.

It would be great if surveys are reliable – the ESM method is costly and annoying, which is why it's so rarely used.

Unfortunately, they're not – surveys are significantly less reliable than ESM results.

I'd prefer the worse vacation, thank you very much.

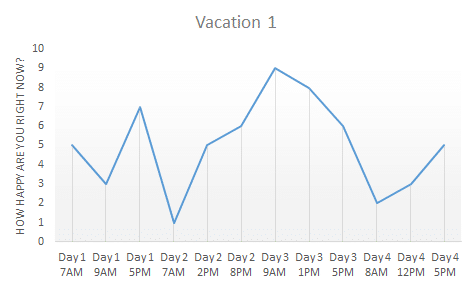

An example – a person goes on two vacations, one for four days, another for eight. Using the ESM, they are asked several times a day how happy they feel. The following data might have been collected:

During which vacation did they experience more happiness? Vacation two – add together their ESM responses, and you get a crude but reasonably accurate measure of total positive emotion. For vacation one the total is 60. For vacation two it's 100.

Yet asked which vacation they would rather have again, many a person might pick vacation one.

Vacation two gave them 66% more happiness, but they'd prefer vacation one.

I simplified the data, but those were the results of a real-world study done of vacation goers – folks consistently made mistakes in estimating how much positive and negative emotion they experienced.7

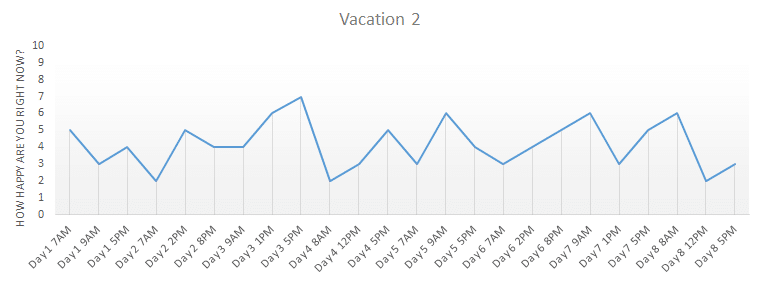

The same result, but in a study of cold water and pain.

Participants were asked to put their hands in painfully cold water three times.

The first time, participants immersed their hands in water 57 °F for 60 seconds.

The second time, participants immersed their hands for 90 seconds. The first 60 seconds were 57°F, and then over the next 30 seconds, the temperature was raised to 59°.

The third time, participants were given a choice – repeat the first immersion or repeat the second.

Participants overwhelmingly chose the second immersion. Yes, they overwhelmingly chose the longer, more painful experience. In case you're skeptical, go ahead and put your hands in 59° water. It's painful.

So what's going on? Because the second immersion ended less painfully, and because the end of an event can influence the color of an entire memory, the second immersion was misremembered as containing less pain.8

Likewise with painfully loud noise, unpleasant video clips, and colonoscopies:9,10

For the first ten minutes, patient B experienced the same amount of pain as patient A. Then the evil scientists extended the operation, giving even more pain.

Patient A experienced almost 50% less pain than patient B, but reported the experience as being twice as unpleasant. WHAT!?

Go ahead – take another look at the graphs. It's real data, and similar to the results of the other subjects in the study.

Why such crazy results?

For patient A, the experience ended at pain level 8. For patient B, it ended at pain level 1. The less painful ending colored his perception of the entire operation – our memory is durable, not set-in-stone perfect forever.

In forming our memory and feelings for an event, only a few pieces of the actual data get used. Specifically:

- The higher intensity moments become deeply embedded; most of the mundane is discarded. A moment of intense joy can transform an average experience into a great one.

- The end of the experience colors the perception of the entire memory. An unhappy ending can ruin an otherwise excellent event.

What this means is that data on duration is getting discarded.

Seven days of happiness gets remember similarly to three; 25 minutes of pain gets remembered similarly to 10.

That's why folks picked vacation A over vacation B:

Going on vacation A made me very happy for three days vs. going on vacation B made me happy for seven days.

With the data on duration deleted, what might have been a difficult choice simplifies – very happy vs. happy.

So if you asked me how my life has been over the past ten years, I'd say really good, despite the fact that on closer inspection, that's false. I spent many of those years afflicted with chronic pain. But because the past few months have been great, and because most of my more memorable experiences are of happy times, my entire memory of the past ten years has been recolored as being more pleasant than it actually was.

You can look at it this way – a significant amount of important information is getting blurred out:

What are the consequences? It's possible that…

Having kids increases rather than decreases positive emotion.

Last year, I wanted to know if having kids decreases or increases happiness, so I read all the research I could get my hands on and wrote a summary. The one-sentence summary – the more kids a family contains, the lower life satisfaction and happiness they report.

It's possible that research is wrong. Indeed, recent studies using the ESM suggest exactly that. It's possible that parents experience small amounts of joy throughout the day, punctuated by bursts of stress and frustration.

In total, they might be experiencing more happiness than before. But recall – the data used in evaluating a situation isn't a sum of the emotions experienced during individual, minute-to-minute moments. It's the emotions experienced during the most memorable and high-intensity moments. For many parents, it's possible the majority of their high-intensity moments correspond to stressful or frustrating experiences.

Some positive psychology interventions are being incorrectly reported as impotent.

If an intervention gives a bit of joy here and there but has no impact on the high-intensity, memorable parts of life, it's possible that the typical happiness survey will fail to capture the effect. Those small bits of joy could be discarded or under-weighted.

Across the board, happiness is being underreported.

How a person is feeling at the moment will color their response to unrelated questions. Someone who is unhappy might report having had a mediocre vacation… even though if you ask them again after they've had sex, they might report that the vacation was wonderful.

Likewise, the environment in which a person is asked about their happiness will influence their response. In this case, a common environment is the mandatory visit to the university lab, where undergraduate students need to go in order to get class credit. I certainly didn't like it – forced out of my way to sit in a room answering dozens of boring questions. I wasn't answering a psychology questionnaire, but if I was, I'm sure I might have underreported my life satisfaction.

Another common environment is a mail or telephone survey. Do you like being disturbed in order to fill out a bunch of random questions? Once again, I expect life satisfaction and happiness might be getting underreported. Perhaps it isn't 15% of Americans who are very happy, but 25%?

Strike Four – Placebo Effects, Over and Over Again

At a high level, there are two kinds of placebo effects – statistical effects, like a reversion to the mean, and mental effects, like the power of positive thinking.

Vitamin C is a good example of the statistical effect.

Vitamin C doesn't actually reduce the duration of colds, but because the consumption of Vitamin C and the peak of the cold sometimes coincide, there is a placebo effect – it appears the treatment is having an effect, when in fact the person is getting better all on their own.

This is why experimental studies have control groups – one group takes Vitamin C, the other takes a sugar pill. Now the real effect is obvious – the Vitamin C has the same impact as the sugar pill (that is to say, zero effect).

Antidepressants are a good example of the mental effect.

Sugar pills often have the same impact as the actual drug. Because neither have an effect and the patient is simply getting better, all on their own – no, the patients not taking any pills at all fare worse. It's because the one effect that shows is coming from the placebo effect – the patient thinks they're taking the ‘real' drug, they expect the real drug to increase their happiness, their subconscious, through a variety of mechanisms, then actually makes them a little happier.

The placebo effect is difficult to harvest, so we want to be sure positive psychology interventions are working for reasons other than the statistical or mental effect.

The statistical effect is not a concern – although some study participants will randomly get happier, others will also randomly get sadder.

The mental effect is a concern – if a participant knows his participation in the study is supposed to make him happier, because of the placebo effect, for a short period of time he might actually become happier.

From having looked through a few hundred positive psychology studies, I'd say this is a serious problem – most studies only control for the statistical effect.

To control for the placebo effect, those in the control group must believe that they too are actually receiving the treatment. Some studies make the effort. For example, in one study:

- One group was asked to keep a gratitude journal. This was the “real” test.

- The other group was asked to write about a time when they were at their best and then to reflect on the personal strengths displayed in the story. This was the “sugar pill”.

This sugar pill was an effective control for the placebo effect because it appears feasible that the exercise could actually increase happiness – the study participants had no way of knowing if theirs was the real or placebo group.

Most studies don't have that.

Instead, they'll have a waiting list. For example, all of the experimental studies I could find on the effects of compassion training on happiness have waiting list control groups. Waiting lists! It's obvious to the participants who's getting the treatment and who isn't! You're either doing stuff or you're on a waiting list. Not effective.

So it's possible my article on compassion is based on incorrect research – it's possible the benefits observed can be traced back to the placebo effect.

Strike Five – There's a Result, Somewhere!

As it stands now, in the field of psychology statistical significance is a stupid concept. All published papers claim 95%+ statistical significance.

That claim means this, “keeping in mind mistakes and statistical anomalies, there is a less than 5% chance that my finding is incorrect.”

Less than 5%? Have these people gone mad?

Despite this 95% statistical significance, most published findings are false and fail to get replicated.

Go through any psychology textbook from the 70s or 80s – your mind will be blown by some of the crazy ideas that had strong “empirical evidence,” like repressed memories or fear of success. Despite 95% statistical significance, nutrition science is still a mess.

I'm hardly the first to make these claims – former American Psychological Association president Martin Seligman broke away and founded Positive Psychology in part to create more accurate research. At first, he might have succeeded, when the field was limited to a few hand-picked scholars. No longer.

In 2011, Using techniques freely employed by psychology researchers, Joseph Simmons “proved” that listening to “When I'm Sixty Four” by The Beatles causes people to misremember their age as something younger.11 With 95% statistical significance, no less!

The simple explanation – he discarded the data he didn't like.

Participants were asked to write down their age twice – once before they listened to the song, and once after. Who likes wasting time at the psychology lab? No one. In their hurry, it's expected that a few folks would make a mistake.

However, for every person who accidentally adds a year to their age, there should be a person who accidentally drops one.

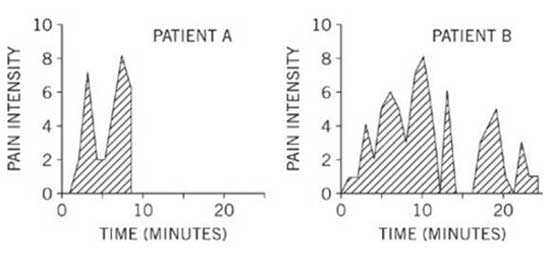

If you want to prove that a coin is rigged and only lands heads, delete the results every time the coin comes up tails:

I'm not talking about being sneaking and pressing the delete key.

Although they've got to get creative, “SCIENTISTS” CAN DO THAT! They can get away with hiding the data they don't like.

Using accepted practice, Joseph hid the data that didn't fit with the hypothesis he was trying to prove.

He deleted the cases where someone listened to “When I'm Sixty Four” and miswrote their age as a year older. With only the confirming data left, a clear, “statistically significant” effect remained —> listen to the song, become younger.

Of course, the statistically significant effect was an engineered coincidence – repeat the experiment, and the relationship would disappear. Unfortunately, many positive psychology experiments don't get repeated.

The detailed explanation – techniques for scientific voodoo.

1. Discarding outliers is common practice, but the process for deciding what constitutes an outlier is flexible enough to allow data sculpting. Joseph discarded data which conflicted with the conclusion he wished to show – just as important – he discarded without needing to report to the reader what he had done. He got away clean with getting rid of 40% of his samples. One method for flexible data deletion is to collect more variables for each data point than is required. Then, to declare a “bad” piece of data, scour through the auxiliary variables until one of them has a value far enough from normal to declare the entire data point an “outlier”.

2. Joseph re-ran the math after each additional sample. Want to prove a fair coin is actually weighted? Stop the experiment after a strong run – for example, flipping a coin 20 times might result in HTTHTTHTHTTTTHHHHHTH, which shows a 50% chance of heads and 50% chance of tails. But if the experiment had been stopped after flip 13, you'd see a 30% chance of heads and 70% chance of tails. (The more scientific might observe that in this coin flipping example, nothing is actually ‘proved', as the data fails to meet statistical significance. That's irrelevant – a more elaborate example would ‘fix' that problem.)

3. Joseph collected data for a large number of variables which he later discarded. With enough data, some publishable relationship will appear. This is why data mining is an often dangerous tool.

4. Joseph “re-ran” the experiment until it produced the results he wanted. For example, if you want to prove that a coin is weighted, flip it 5 times – if it comes up the same each time, you know with reasonable confidence that it's weighted – after all, the chance of that happening by chance is just 3%. But if you really want to prove that the coin is weighted, you can run the experiment 30 times.

Due to statistical coincidence, it is now likely that for at least one of those experiments, the coin will land the same way each time. Here's the magic – you can delete all of the failed experiments. Instead of an accurate aggregate, “I ran the experiment 30 times, only once did the coin land the same way each time – combining the data, my hypothesis is obviously false,” researchers give, “I ran the experiment once, there was a statistically significant effect.”

For example, Joseph had participants listen not to one, but to three different songs. Due to chance, it's likely that for one of these songs, participants will miswrite their age in the way that he wants. But one out of three isn't convincing. So he deleted the data for the songs which produced no effect. One out of one? Statistical significance!

Furthermore, Joseph could have run his experiment ten times, with failure each time except the last, and report only the success. In the real world, this is a common occurrence – ten different research teams might be trying to prove some idea. They might each run two experiments each. By chance, it's highly likely at least one of these experiments will have a statistically significant result, even if it shouldn't (e.g. roll two dice enough times, and you'll get snake eyes). Because research journals only publish positive results, we'd never know about those 19 failures.

Another good example is the Seer Nostradamus. He made so many predictions about the future (a few hundred), that it's extremely likely that at least one will have vaguely come true.

Strike Six – Everyone Says I Should Be Happy… I Guess I Am?

According to happiness surveys, Denmark is the world's happiest country. According to a conversation I had with a Happier Human reader from Denmark, it's not that they're actually happier, but just have lower standards, and have no idea what they're missing.

I think that's untrue – Denmark has a lot of good things going for it. But in many other situations, social expectations are a serious problem.

According to the surveys I could find, over 80% of Americans report being satisfied with their job.12,13

WTF!?

For every person I've met who says they like their job, I've met at least two who say they want something more.

Either people like to complain for the sake of complaining, or the job satisfaction data is wrong.

I think both are true:

- There's a myth that there's a perfect job waiting around the corner, that will make everything better.

- For better or worse, there's a belief that nine to five drudgery from hell is normal.

People are unhappy at work, but because unhappiness is the expectation, they still report being satisfied with their job.

This is why Millenials have such a big problem – they have completely different social expectations. They expect the world to bow to their greatness. When it doesn't, they become unsatisfied.

When someone asks you how you're doing, how often do you respond, “bad?” Due to social expectations, the correct response is “good,” even when that's a lie. Because of this effect, I expect that some surveys, like job satisfaction surveys, overestimate happiness and life satisfaction.

Gratitude journals – objective improvement or shifting social expectations?

The gratitude journal exercise produces objectively measurable changes, like improved sleep. It also causes people to become more likely to mark down “very happy” instead of “happy”. It's possible that the gratitude exercise doesn't actually increase positive emotion as much as the results would claim – instead, social expectations shift, “I ought to be grateful for what I have, I ought to mark down that I'm very happy.”

Let me note – this is a more complex issue than it might seem. Life satisfaction and positive emotion are separate life components. It's possible to experience lots of negative emotion, but still be highly satisfied with life. Likewise, it's possible to experience lots of positive emotion, but be unsatisfied with life. So it's possible that the gratitude journal exercise increases life satisfaction (which is good), but has an overstated effect on positive emotion (which is bad).

There are lots of problems.

Happiness is only one of the many things we care about. Even then, because of social expectations and information loss, surveys do a poor job of measuring a person's balance of positive emotion. And most studies have terrible control groups. And many follow methodologically precarious procedures, which virtually guarantee finding some publishable finding, even in the absence of real discovery. Lots of problems.

It's actually depressing for me to write them all down like that in the same paragraph. I love science! I wish I could read an experiment's result and trust in its accuracy. I can't – I have to spend time reading the details of the experiment.

But even without spending time checking for mistakes and errors, despite the flaws, many research papers are accurate enough to provide value.

How can I say that? Research surveys don't need to be objective or accurate to be useful. They only need to provide information which can't be found anywhere else.

They do. Specifically, if a person's response to the happiness question is correlated with other, more concrete measures which we care about and can be used to predict future outcomes that matter, that response is providing useful information.

Evidence of Validity

I care how long my colds last and how often I'm sporting a smile.

So if the response to the question, “how happy are you these days?” can be used to predict how long my colds will last and how many times a day I'm liable to smile – BINGO. If a positive psychology study shows that a particular intervention makes it more likely that a person will respond “very happy,” then by extension, they're showing that the intervention improves a person's resistance to colds and increases the likelihood that they'll be smiling.

What sorts of things can your response to the happiness question be used to predict?

- How quickly you'll recover from a cold.14

- How quickly you'll heal from a wound.15

- How likely you are to generate brain activity in the regions associated with pleasure.16

- How often you smile, and when you do smile, how likely that it's a real one.17

- The quality of your sleep.18

- And more…

Some of the relationships are weak. Others are methodologically uncertain – I left out the studies with criticisms, like the “Nun Study”, which showed that those nuns who were happier at a young age lived longer.

What you've got left is a large number of life components weakly related to the results of happiness surveys. More would be better, but for now – this is enough to work with.

If gratitude and social activity can increase my self-reported happiness, and if self-reported happiness is related to many things I care about, even if only weakly, I'd be a fool not to increase my gratitude and social activity. I'd be a fool to focus on self-reported happiness as the be-all end-all. But I'd be a fool to ignore the information positive psychology studies provide.

The measurement of happiness is a hot mess, and that's okay.

Measuring Happiness References

2. The Optimal Level of Well-Being

3. Some Key Differences Between The Happy Life and The Meaningful Life

4. Lucas, R. E., & Clark, A. E. (2006). Do people really adapt to marriage? Journal of Happiness Studies (JoHS), 7, 405– 26.

5. F. Strack, L. Martin, & N. Schwarz, European Journal of Social Psychology 18, 429 (1988).

6. Thinking, Fast and Slow

7. A test of the peak–end rule with extended autobiographical events

8. When More Pain Is Preferred to Less: Adding a Better End

9. Kahneman, D. (1999). Objective Happiness. In Kahneman, D., Diener, E. and Schwarz, N. (eds.). Well-Being: The Foundations of Hedonic Psychology. New York: Russel Sage. pp. 3–25.

10. Duration neglect in retrospective evaluations of affective episodes

11. False-Positive Psychology: Undisclosed Flexibility in Data Collection and Analysis Allows Presenting Anything as Significant

12. General Social Survey

13. Employee Job Satisfaction and Engagement, A Survey by SHRM

14. Emotional Style and Susceptibility to the Common Cold

15. Psychoneuroimmunology: Psychological Influences on Immune Function and Health

16. Making a Life Worth Living: Neural Correlates of Well-Being

17. Developments in the measurement of subjective well-being.

18. Wilson, W. R. (1967). Correlates of avowed happiness. Psychological Bulletin, 67(4), 294.

19. The Effect of Feeling Good on a Helping Task

Hey Britt, thanks for stopping by!

At this point in my journey, I agree. When I first encountered positive psychology two years ago, I was much more dogmatic. Empirical science vs. bias ridden anecdote? Duh science! But then I slowly learned that the science has lots of faults too.

Give them scientists a few hundred million dollars and a decade or two, and I think the suggestions would be MUCH better. Happiness would be broken down into subcomponents. Suggestions could be more personalized. Measurement would be more accurate.

Theoretically, I think it’s possible to objectively and accurately measure happiness. Practically? We’re far far away.

Wow. What a post. I think I have an inkling of what it is like to sit through a varsity lecture now…I never went to varsity, so I am only assuming here. It’s an interesting topic but boy do you make it look like school work with all the graphs and stuff. If I may be so forward as to make a request? For those of us laymen types, could you post less involved and complicated posts on these rather interesting topics? I feel mildly disorientated after trying to wade through some of your posts sometimes, which is a pity because your topic choices are super interesting. I just wish I can understand what you are saying. I apologize if I sound critical, I swear I’m not, I just can’t follow you most times, but I would love to.

Sorry Janet! The reason I’ve got all the graphs is to help make the ideas easier to understand – not to make it boring like a lecture.

But you’re right. I have to find a better method of explaining things. One that retains the complexity I love, but that is more accessible and easily digestible. I don’t want to simplify too much, because then I’d be posting the same surface level monkey garbage found everywhere else… but obviously this stuff is useless if most folks can’t follow it.

Thanks for the feedback 🙂

Hi Amit

Great blog. Interesting, useful, informative.

Liked your point about most research having a waitlist as control, that is not likely to be effective. Happily, the latest research from Richard Davidson “Compassion Training Alters Altruism and Neural Responses to Suffering” 2013, appeared in Psychological Science, does have the control group actually doing something! So maybe we’ll see a bit more of that in future.

Adiba

Thank you for sharing that reference! It makes me happy to see higher quality research being produced 🙂

I just took a quick look at the article you mentioned – I really like it. Reappraisal = active control. It seems obvious that compassion meditation is awesome – but it’s nice to know in exactly what ways and by how much.

Adiba – I love what you’re doing with Bidushi! Let me know if I can help in any way – someone who popularizes useful scientific information in a way that doesn’t drastically distort the underlying knowledge will always be a friend.

It just seems like measuring happiness would be so much harder than other things. Take weight loss, for instance. You can step on a scale and get an objective measure for weight – it’s right there on the scale. For happiness though, it’s all subjective. Who’s to say that how I measure happiness is similar or different from how others measure it.

Then there are those differing definitions of what happiness is. A lot of people consider happiness to be different things. Are we all measuring on different scales then too?

It just seems so complicated. If we could work out the kinks and wrap our heads around it all we could make a huge leap forward in finding happiness for all.

Yes sir, I 100% agree.

It’s unfortunate that most of the folks trying to tackle the kinks and wraps seem to be philosophers (http://lesswrong.com/lw/4zs/philosophy_a_diseased_discipline/ on why I think that’s a problem).

I would prefer a multi-disciplinary team including folks like neuroscientists, psychologists, economists, mathematicians, computer programmers, and more.

On the one hand, I think getting a weakly accurate measure of happiness is easy, and I wish people were more willing to trust positive psychology research. On the other, I think getting an objective, fully accurate model – one which breaks things down to concrete formulas and rules – will be one of the greatest challenges of the next few decades. I also think – like you – that it would make a huge leap forward in finding happiness for all.

If policy decisions could be framed in terms of objective happiness – shit, that would be amazing.

Great post. I also say to people again and again that happiness is very subjective because what makes one happy (for example money or health) might not be what someone else is aiming for as ultimate happiness.

And therefore, a very difficult thing to measure.

Thanks for sharing.

Thanks!

Right. If were were just talking about positive emotion, it could be done – we’re got fMRI machines which can more objectively track the rise and fall of emotion. But ultimate happiness? Too complicated. Which is why when an AI programmer tells me that he thinks he knows how to program human values into an AI, I think he’s a little crazy.

Really good points. It’s so funny you mention Denmark, I had no idea that they claim to be the happiest country. I am originally from Spain but moved to Denmark a year ago, and I can definitely tell you that people here aren’t as joyful or kind generally, especially in the fall/winter, you won’t see a lot of smiles.

Haha, you’re now the fourth person I know from Denmark who has made a comment like that. Thanks for sharing your experience!

It’s not that they claim to be the happiest country, but that there have been global happiness surveys, and that folks in Denmark tend to mark down the highest results (e.g. “How happy are you, from 0 to 10” – folks in Denmark are more likely to mark down 7 or 8, rather than 5 or 6). I think those surveys must be missing something, because like you, I’m skeptical that Denmark is actually the best place to live in the world.

This reminds me of a quote from Ed Diener in the HAPPY Movie. It was something to the effect of how people told him that it was impossible to measure happiness, yet there were many studies that were measuring sadness and misery. All of the arguments against measuring happiness in this blog post can be inverted and used precisely against measurements of depression, anxiety, and any other number of psychological maladies. The question here is not about measuring happiness (or any other emotional state or psychology trait or whatever) – the question should be “Is self-report the best that psychology can do?” And the answer seems to be, “Right now, yes, but stay tuned…”

Excellent insight, thank you for commenting!

I would imagine that sadness and misery are easier to measure than happiness, only because we’ve been studying them longer and because they have more noticeable effects on a person’s life. But even then, inversion does make sense. How can we claim to objectively measure sadness, when we don’t quiet understand its opposite – happiness.

In the eyes of lay-people, I think the question more is, “Is mass aggregated self-report more accurate than cultural wisdom, intuition, memory based decisions, and the like?” I think the answer is yes, which is why this blog exists! But like Diener, I look forward to improved methods and understanding. Experience sampling is a good start.

Anyhow, happy new year, and thanks for reminding me that I need to watch the movie HAPPY 🙂

Wow, quite the comprehensive post you have put together Amit!

I think it’s hard to measure happiness because it’s highly individual, and it also depends on how we train our brains. You can enjoy doing a certain activity, and then train yourself to like something else over time. That’s been the story of my life for the past 2-3 years.

I like completely different things now compared to before.

I also dislike it when people borrow authority by quoting that famous study saying that you don’t get happy by earning money past a certain income level. The reason I don’t like it is because money represents different things to different people.

Ofc I’m not directing this last part specifically towards you!

🙂

Comprehensive is the name of my game. Although I’m reconsidering – shorter seems to get more traffic.

Anyhow, you raise some interesting points Ludvig!

You raise the question of spread. Although the average person reports a 10% increase in life satisfaction for every doubling of income, there will be some who report a much smaller increase, and some who report a much larger increase. So actually, the spread is not so large here – most people don’t really report larger increases than 10, 15, 20%. This is because wealth has some negative effects on life satisfaction (like decreased ability to savor).

On the other hand, even if life satisfaction isn’t increasing, even if mood isn’t increasing, that doesn’t mean happiness isn’t. Money represents different things to different people… because happiness means different things to different people.

“You can enjoy doing a certain activity, and then train yourself to like something else over time. That’s been the story of my life for the past 2-3 years.”

Absolutely. People grossly underestimate their ability to cultivate enjoyment for things they currently hate (a new food, a new hobby, a new job, etc…). And this goes a step forward. People in the middle-ages would never have imagined electrocuted pieces of metal (TVs) giving them happiness. In the future, who can say what we will want and enjoy?

GREAT points Amit.

I think length depends a lot on your target audience. But your target audience is hard to know until you’ve established yourself… So it’s a little bit like circular reasoning.

But in general. Yes short is better.

In the future we’ll be constantly hooked up to instant gratification by means of some mega-iPhone hologram type thing! 🙂

This is deep.

I’ll need to reread this because this kind of post which is well-researched needs time to be digested. Happiness is subjective and after reading your post my conclusion is different – happiness is subjective and complex.

Thanks for the post, Amit.

I’m glad I was able to change your perspective!

Happiness is subjective because it is complex.

At the end of the day, we’re all humans. We’ve mostly got the same genetic code and the same basic wants, desires, and values (e.g. compare a human with another human, vs. a human vs a dog – in that perspective, us humans are fairly similar). But because happiness is complex, those basic desires and values get expressed and interpreted in slightly different ways, causing the subjectiveness.

But I think that with a deep enough understanding of happiness, it would no longer be subjective.